The Korean Bar Girl Turned into a Giant Snake; Stories At War

Is the Easter Bunny a Christian deity? How about Father Christmas? Of course they are both in the cannon of Christian symbolism, but do we believe in them? Well, yes and no, many children of Christian families do, regardless of whether their parents believe or not. Father Christmas is loosely based on St Nicholas, but he’s more like a transformation of pagan Winter-gift-giving spirits from European Folklore. And the Bunny, with its colourful eggs, judging the behaviour hopeful children? Well this character also hails from pagan Springtime beliefs, and seems to have slipped into the Christian tradition via stone carvings of rabbits in churches. The reason I’m bringing these examples, is because I’ve always been fascinated with the blurred boundaries between cultural stories we respect, and those we don’t respect.

I see each religion as a big dress which is ornately patterned with story spirits - the more famous and celebrated the stories are, the larger their motif appears. But tucked away under each dress there are hundreds of thousands of little stories which are fighting to climb up the legs and sew themselves into the fabric. As the dress is walked around, stepping between communities and nations, more and more little local stories climb up the stockings and into the pantheon, hoping to get respect, elevation and survive. When fantastical stories are respected we call them religions, but when they are not we call them folklore, and these narratives fight a constant battle for our attention. Polytheistic religions are defined by the collection of spirits and deities, carried over by trade and diplomacy, but monotheistic religions often define themselves by the rejection, persecution and ridicule of false-Gods.

Christian holiday postcards (1907)

“Green Man” sculptures from British Churches

I was told a story by a shaman in Korea in 2014. When the first Christian missionaries arrived on the shores of Korea, they sought an audience with the local shamanic leaders known as Mu-Dang. The missionaries presented a statue of Jesus and explained the virtues of their God. The shaman thanked the missionaries for their statue and agreed that their God sounded very powerful indeed, and would make a great addition to their pantheon, placing the statue respectfully inside a shrine alongside votive images of Bodhisattva, Princess Pari, The Ten Kings, and others. Of course this is not what the missionaries wanted - they wanted to eradicate all the other stories. But of course humans do not work that way.

Do you know the “Green Man”? In the UK he appears in many of our Christian churches; a man’s face with leaves and flowers bursting from every orifice - he is not Christian, but a pagan God, and when the Christians came to rip apart his places of worship and burn down his sacred trees, he climbed up their legs and sewed himself into the fabric of their churches. Good stories are very hard to kill.

A far more controversial point would involve a discussion of Apollo climbing up the legs of Christianity and disguising himself as Jesus Christ himself - “The Good Shepard”, “The Light“, “The Teacher“, ”The son of God,” the vision we now have of Jesus is undeniably modelled on his pagan predecessor.

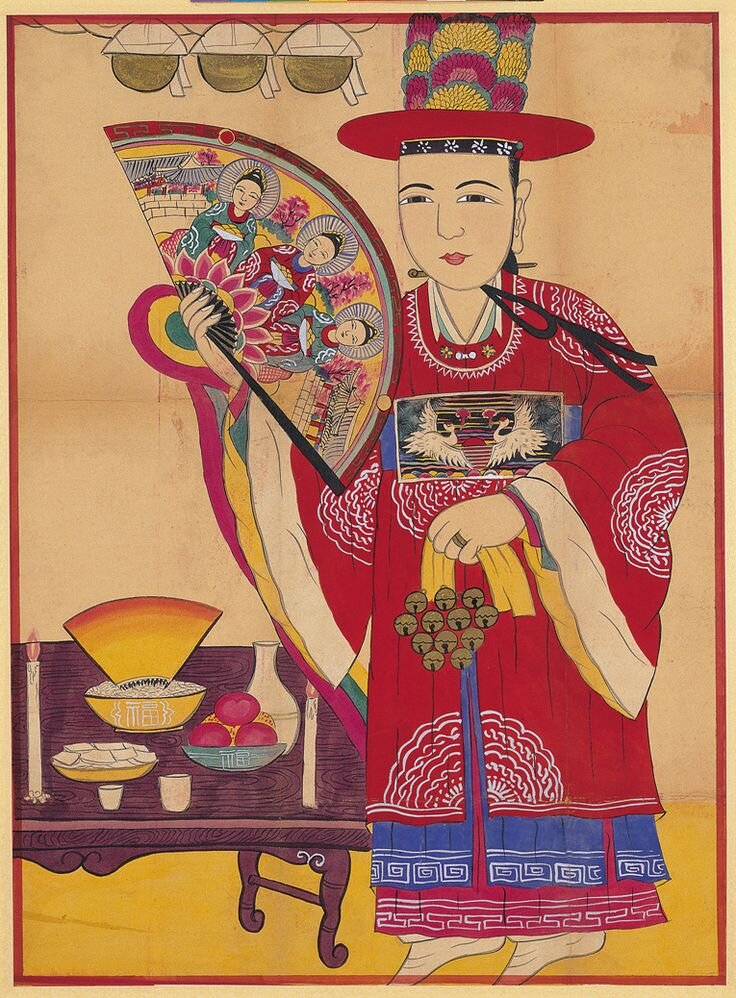

In 2014 I began researching Korean Shamanism for a series of artworks I was releasing with Seung youn Lee, as The Bite Back Movement. However, in Korean shamanism I’ve always had a really hard time differentiating the stories and sprits which are believed, and those which are not. As with all polytheistic systems, there are many Gods and spirits which have gathered into an infinite pantheon which is forever changing - but I couldn’t separate the Father Christmas from the Saint Nicholas - specifically, which stories were perceived as true and which were seen as fairytales. I still don’t know - I asked many people about many characters and spirits, but never got straight answers, and found very little English-language literature on the subject, and my Korean is… not great...

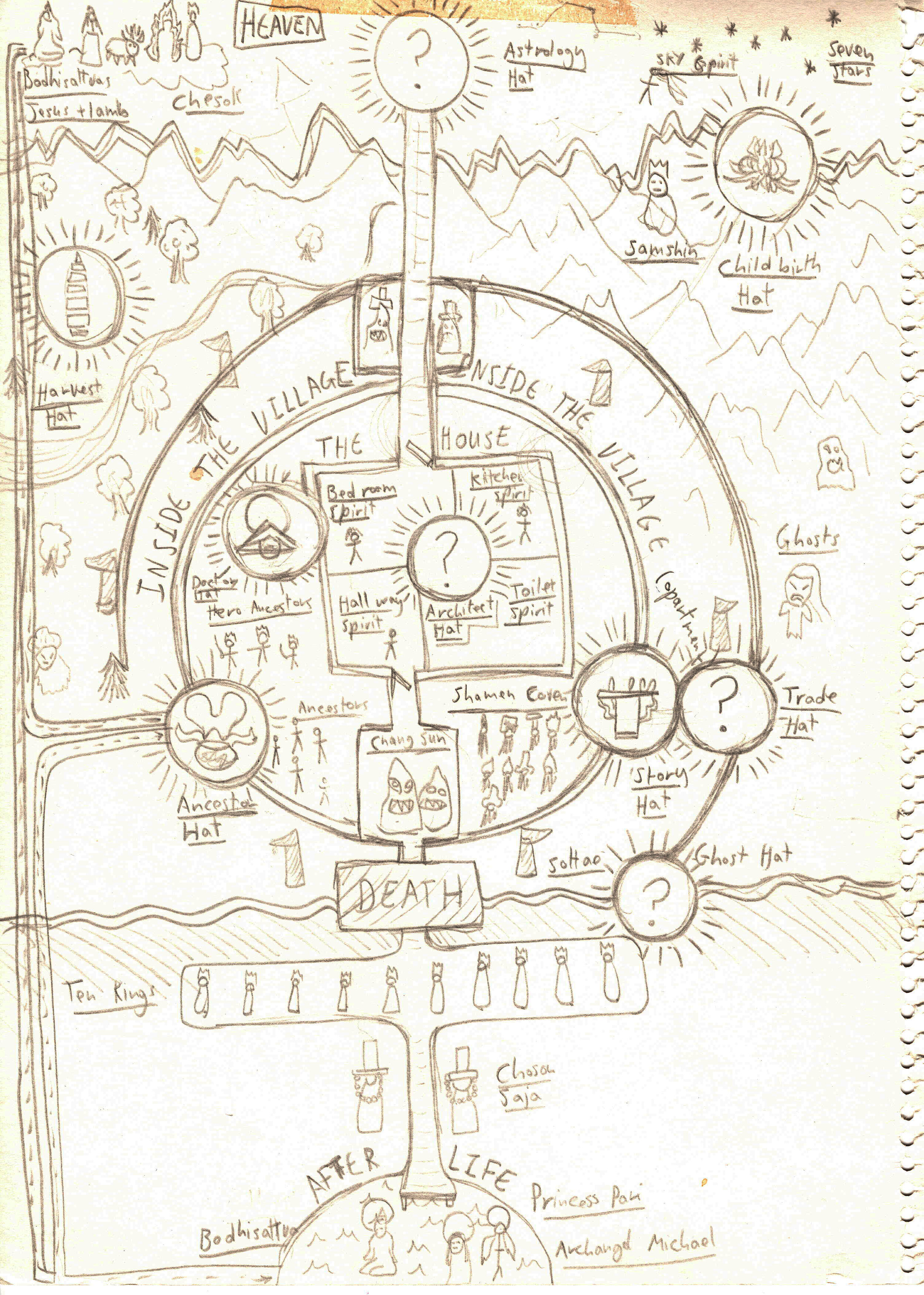

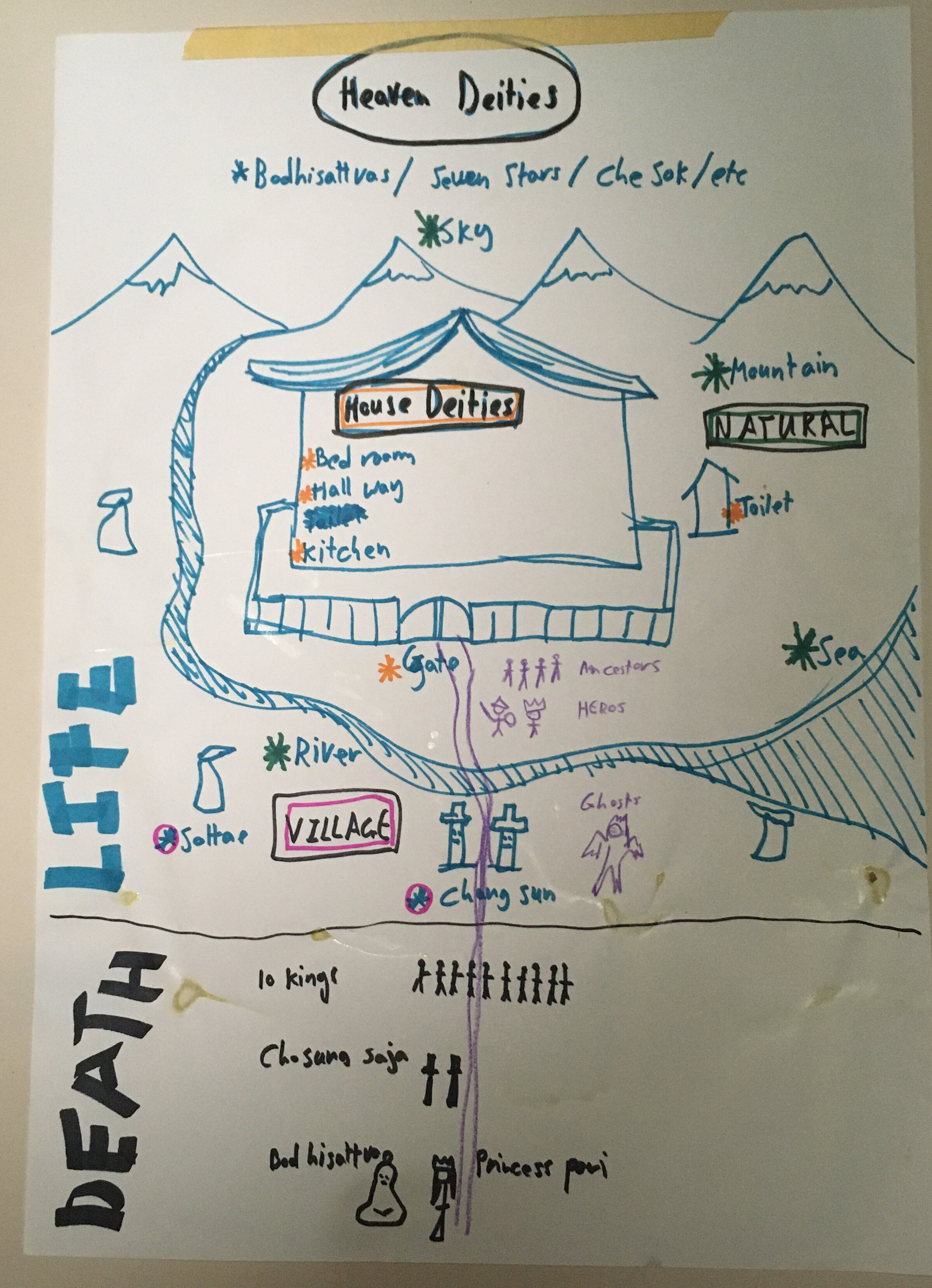

However, from all the stories I found, I tried to understand the types of spirits. There are:

Gods and spirits in the mountains, rivers and natural features of the landscape (such as Grandmother Samshin)

Gods and spirits in the clouds, sky and stars, a realm which I think doubles as Heaven (such as Bodhisattva and Princess pari)

Guardian spirits at the boundaries of villages (Sottae and Grandparent Jangseung)

House spirits in the hallways, kitchens, toilets, bedrooms, entrances, roofs, and other crevices of architecture

Ancestor spirits of deceased family members

Malevolent ghosts who were formally ancestors, but have become wild because no one honoured them, and they forgot their names

Hero spirits of celebrated ancestors, elevated a bit like saints

A group of deities called the “Ten Kings“ who reside over Hell

Spirits who wonder between the worlds of living and dead (such as the Choson Saja and Kokdu)

Regional spirits who protect or represent townships and villages

Goblins who cause mischief (Dokkaebi)

Magic cat creatures (Haetae)

Angels who pass between heaven and the human world, sometimes sleeping with humans and having children, sometimes banished from heaven and becoming centipedes or other insects

Animal spirits who speak Korean and bring wives to lonely men

Animal spirits who relentlessly try to turn into humans by completing tasks (Mother bear of Dangun, founder of Korea), or eating their body parts (Kumiho, mice in general)

Within these categories I found hundreds of stories, some of which were apparently believed to be true, and others which were not. In my confusion I made many attempts to draw maps for the spirit types and where they resided. But alas, the Korean academics and theologists I showed these to were mostly amused and bewildered as to why I might make a map of such a thing:

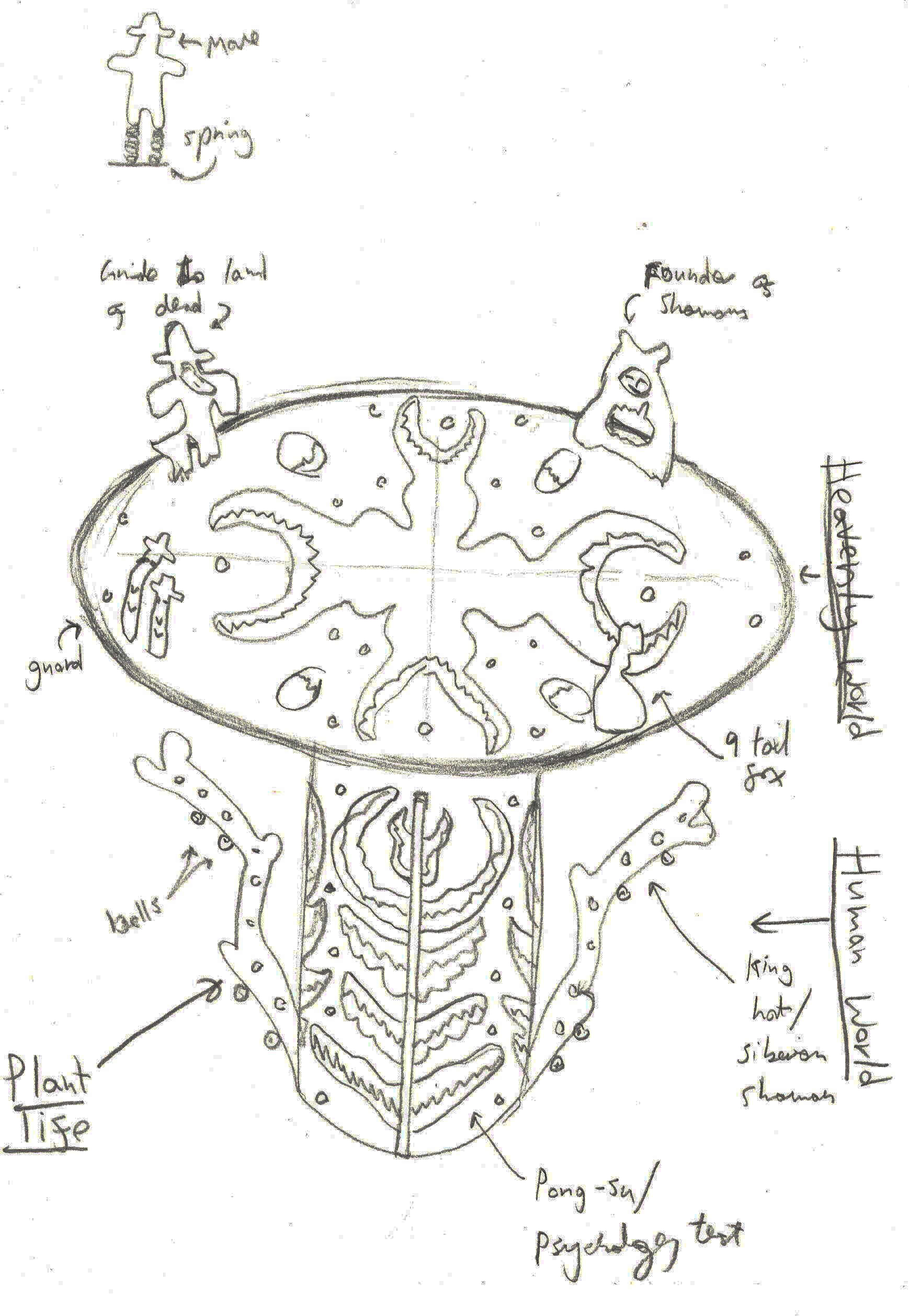

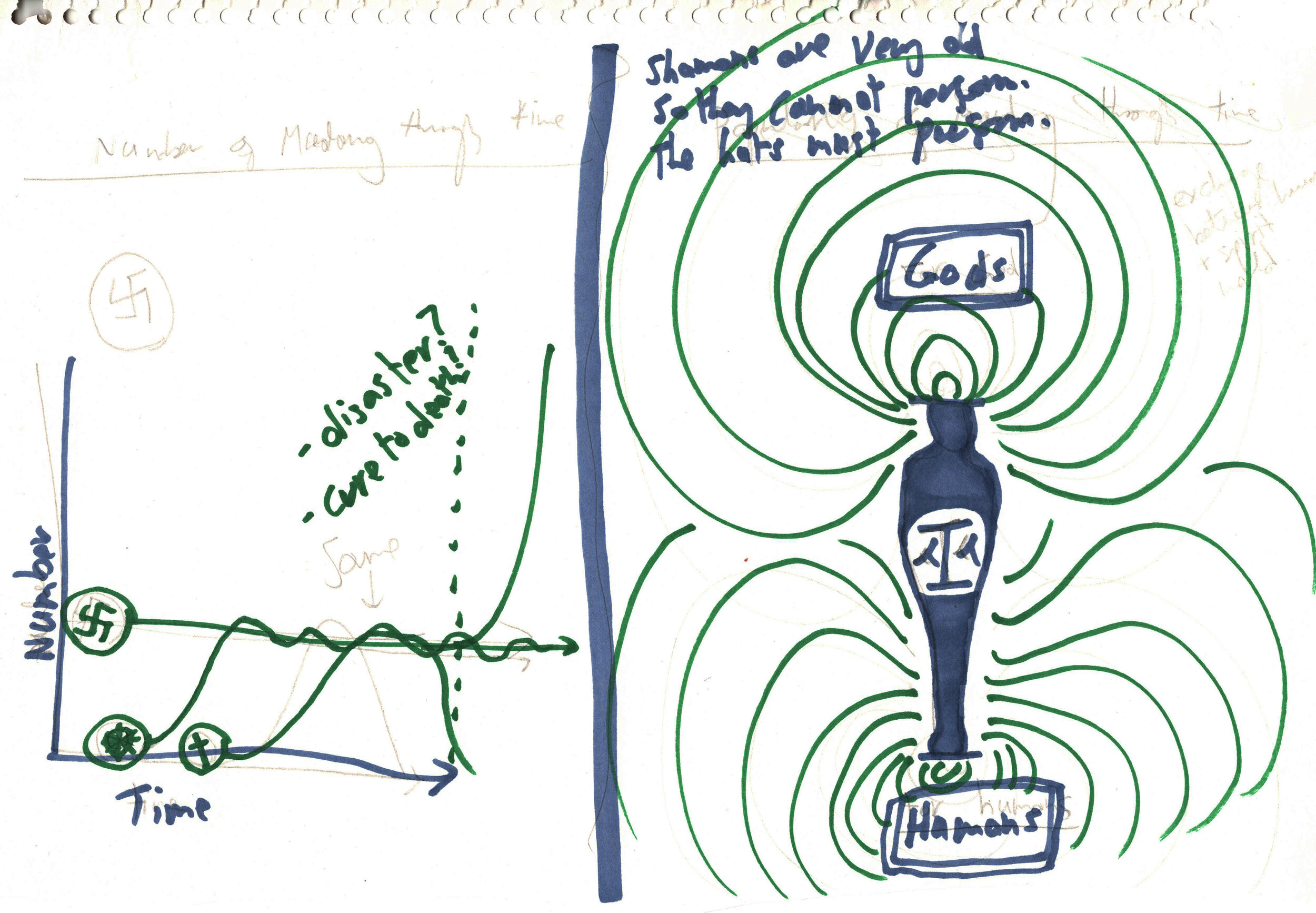

Mu-Dang traditionally bring communities together by telling these beautiful stories, or singing them in Pansoori performances. So eventually I gave up trying to differentiate which stories were believed to be true and which were seen as fairytales, and I just tried to honour the idea of the stories regardless; the story spirits. I illustrated and welded the “Crown of Stories” from steel, a sculpture which was designed to be worn as a hat and performed in.

The overall design plays on the traditional Mu-dang hat, flipped upside-down. I illustrated the pattern of the surface following the traditional belief in the harmony of landscape, pungsu. The top of the crown opens out into a stage, on which the story spirits reside. The hat is supported by plants which reference the shapes of Korean Silla Crowns, and the flat metal construction of the Crown also references this.

This artwork was the begining of a series that myself and Seung youn embarked on, creating crowns and slippers for an imagined futuristic sect of Mu-dangs in the year 2100 AD. They totalled 9 sets, and 3 of these had accompanying films. Please check these projects out here:

Earlier this year I released a Chiffon silk scarf in my shop (left). This scarf has a special place in my heart because it depicts many of my favourite story spirits from Korean folklore. The illustrations are directly taken from my artworks ‘The Crown of Stories’ and the Pollock-God permanent installation sculpture I made in Cheongju. I’ve written about three of these stories below:

A. Cow-people

There is a common saying in Korea, that if you engage in physical activity directly after eating, you will transform into a cow, and might be mistakenly eaten! I drew a couple who became a cow, but they are quite happy to be bovine!

B. The Founding Bear

A tiger and bear prayed to the Lord of Heaven, Hwanung, to become human. He gave them 20 cloves of garlic and told them to stay in a cave out of sunlight for 100 days. The tiger gave up after 20 days, but the bear persevered and transformed into a young woman. She then prayed under a sacred birch tree and gave birth to Dangun, the founder of Korea. This bear is said to be the first Mu-Dang of Korea.

C. The Angry Snake Bar-woman

One day a man was out hunting and he saw a hungry snake in a bird’s nest, about to eat the unguarded eggs. The man kicked the snake away, and the poor thing disappeared off hungrily. A few years later the man was in a bar drinking, and suddenly the doors and windows slammed shut. The bar girl transformed into a giant snake and said to the man “I am the snake who went hungry that day! Unless you can make the bell at the top of the mountain ring twice, I will eat you!“ Just as the man began to panic, the bell was struck once, and then twice, and the snake girl was forced to flee. He later learned that the mother and father birds of the eggs he’d saved from the snake had overheard and flown into the bell out of gratitude. In order to save the man’s life, they ended their own. And the poor snake girl went hungry again…