There Are No Landlords in Utopia. (1 of 2)

This blog post is the first of two about Utopia, Thomas More’s seminal book from 1516.

I have always been fascinated with the idea of Utopia. Originating from Thomas More’s 1516 work, the promise of Utopia sits somewhere between fantasy and administration. On one hand, Utopia is fantastical because we cannot quite believe that humans can effectively organise equality. On the other hand, utopic ideas often call for the redistribution of resources we already have. It seems at once achievable and impossible. More’s Utopia was a staggering form of Medieval proto-science fiction which gave rise to a new genre of satirical writing. It is unapologetically sharp, referring to the structure of English society in the 16th century as a “conspiracy of the rich”. The premise of his book is simple; our societies suffer from bad management. But what is the price of implementing a Utopic system? Freedom, perhaps? My interests lie in the urban infrastructure, housing, architecture, art and culture in More’s Utopia.

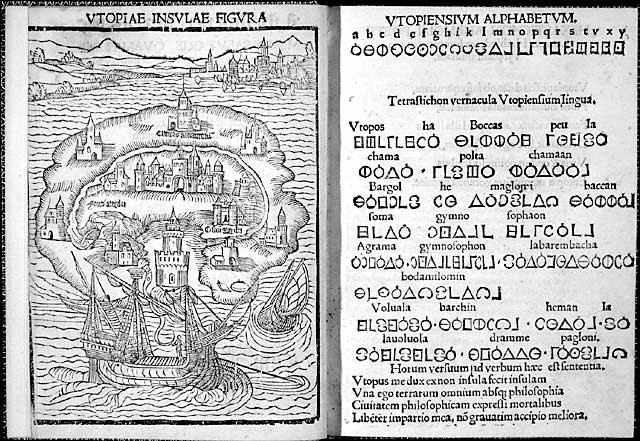

Libellus veer aureus ned minus salutaris quam festivus de optima reipublicae statu, deque nova insula Utopia, Louvain (1516).

Sir Thomas More, Hans Holbein, the Younger (1527).

Messy Thomas More.

Over 500 years ago Thomas More coined the term Utopia with his book of the same name. Utopia translates from the Greek words “ou” and “topos” to mean “not a place” - and More’s pseudo-anthropological work weaves together elements of fiction and nonfiction in his vision of a seemingly perfect society. It is ultimately a political and social satire which sought to critically examine wealth inequality, political corruption, religious intolerance, and flaws in the legal system at the time.

The first peak of the book is an unexpected treat at the start where More gets messy and preemptively attacks his critics, explaining that they may criticise his work, but at least he has some work to criticise, of which they have none:

“They seize upon your publications, as a wrestler seizes upon his opponent's hair, and use them to drag you down, while they themselves remain quite invulnerable, because their barren pates are completely bald”.

For me, this scene conjures images of bald drag queens ripping wigs off one another. More then turns on his readers, calling them ungrateful:

“[...] some readers are so ungrateful that, even if they enjoy a book immensely, they don't feel any affection for the author. They're like rude guests who after a splendid dinner-party go home stuffed with food, without saying a word of thanks to their host.”

Now, any reputable artist has likely encountered a mercenary clutch of art-world-professionals at their exhibition openings, primarily there to drink the gallery's booze and interrogate the artist about their material expenses. Let’s just say that I can relate hard, and after More’s opening tirade, I was primed to wolf down anything he was serving. Luckily Utopia only gets better from there, as More proceeds to lambaste the rich, the clergy and the Catholic Church, the owners of capital, those with passive incomes, and all the governments of Europe. Indeed, Utopia is often referred to as one of the most influential books in history, and was clearly very radical in 1516, espousing progressive ideas on the rehabilitation of prisoners, religious pluralism, the equal distribution of capital, gender equality in employment and dress, emphasis on education, restraint on monarchic spending, and the abolition of private property! Remember, this was the time of Henry VIII, and More was going full proto-communist, attacking corruption and inequalities in his own time. The messaging in Utopia can be seen as relevant even in the context of today's British government; currently being led by a billionaire Prime Minister with business ties to enemy states; with billions of pounds being funnelled into the secret offshore trusts of Conservative Ministers, and most importantly, having been criticised as 'patently corrupt' by Carol Vorderman. Despite the heavy subject matter, More still manages to keep the tone light.

From the outset, Utopia feels quite playful, starting with pictograms of the fictional Utopian alphabet and poems written in this language, which remind me of the secret languages I made as a child. It then goes on to some letters between More and his friends which supposedly verify Utopia’s existence, but in reality, were fabricated to corroborate the story.

The rest of Utopia is divided into two books, the first of which describes socioeconomic debates between himself, a fictional traveller called Raphael Hythloday and another friend called Peter Giles, who is a real person. Within this chat, Hythloday describes a dinner he attended which was hosted by the Archbishop of Canterbury and attended by a sceptical lawyer and a number of bickering clergymen. Hythloday has apparently been to a faraway country called Utopia, and proceeds to describe that place in the second book.

Throughout Utopia, Hythloday serves as the mouthpiece for most of More’s criticisms of England. In this way, the framing of Utopia is written as a chat, within a chat, within a chat, within lots of chats - and presented as quite removed from the opinions of More himself, who’s character often disagrees with aspects of Utopia in the book. This was probably in a bid to keep his head - which was eventually lopped off in 1535 when he was decapitated for treason.

Pieter Gillis, Peter Giles (1486).

The Housing Crisis.

One of the most striking issues discussed in Utopia is Hythloday’s derision of landlords, who he discusses as “a few greedy people [who] have converted one of England's greatest natural advantages into a national disaster.” He specifically criticises the rental market and the idea of profiting through passive income and stowed capital. Hythloday explains:

“Well, first of all there are lots of noblemen who live like drones on the labour of other people, in other words, of their tenants, and keep bleeding them white by constantly raising their rents. For that's their only idea of practical economy - otherwise they'd soon be ruined by their extravagance.”

This is a relatable issue since UK renters spent an average of 34% of their incomes on housing costs in 2021-22, compared to only 9% spent by mortgage holders.

In other words, renters are currently paying four times as much of their incomes on housing than homeowners - and they don’t get to keep the house in the end! The system is clearly rigged. Our hero Hythloday goes on to discuss the hoarders of capital in more general terms:

“And now, what about those people who accumulate superfluous wealth, for no better purpose than to enjoy looking at it? Is their pleasure a real one, or merely a form of delusion? The opposite type of psychopath buries his gold, so that he'll never be able to use it, and may never even see it again.”

I believe this sentiment to be both spicy and accurate. It is important to mention here that I read the Penguin Great Ideas edition of Utopia, which was suspiciously translated from Latin with the inclusion of terms such as “capitalism”, “communism”, “sociopathy” and “psychopathy”, none of which were existing terms in 1516. Hythloday then goes into more detail about how tenants are abused with forced evictions:

“They're either cheated or bullied into giving up their property, or systematically ill-treated until they're finally forced to sell. Whichever way it's done, out the poor creatures have to go, men and women, husbands and wives, widows and orphans, mothers and tiny children.”

Tudor house, circa 1500.

According to a report by The Guardian this year, more than 100,000 families in England are living in temporary accommodation, including over 125,000 children, due to homelessness and forced eviction. This is the highest rate in 20 years. The charity Shelter reports that 24,060 households were threatened with homelessness in England as a result of Section 21 no-fault evictions in 2022, and Novara Media reports that the housing charity Safer Renting found 7,778 illegal evictions took place in 2021, with only 11 cases being investigated by the police.

Warne's National Nursery Library (1870).

The Venetian model city of Palmanova from Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg (1572-1680).

In fact, tenant rights in England have been uniquely worse than most of Europe, since 1988 when the Section 21 Housing Act made it possible for tenants to be evicted with just 2 months' notice without reason. By comparison, Italy, Belgium and Ireland - give tenants between 3 and 10 years of protection according to the BBC, making our own ruling body sound similar to the “greedy, unscrupulous and useless” nobles of 1516. Hythloday then cites Plato’s discussion of private property and posits that:

“you'll never get a fair distribution of goods, or a satisfactory organisation of human life, until you abolish private property altogether. So long as it exists, the vast majority of the human race, and the vastly superior part of it, will inevitably go on labouring under a burden of poverty, hardship, and worry.”

This discussion sets the scene for book 2 in which Hythloday describes how the Utopian urban environment is structured to avoid these abuses of power. Up until this point, I pretty much agree with all of More’s critical discussion of England, much of which is depressingly relevant today. After 500 years, it’s enough to make you wonder whether the British enjoy punishment - and these days we are even voting for it! However, it is with the production of solutions that I begin to disagree intensely with More, largely due to his equation of art to elitism. Please continue to my second blog post on Utopia…